Scientists in Peru have announced a new contender for the heaviest animal in Earth’s history.

While today’s blue whale has long held the title, researchers said on Wednesday that fossils of a creature unearthed in Peru called Perucetus colossus could tip the scales.

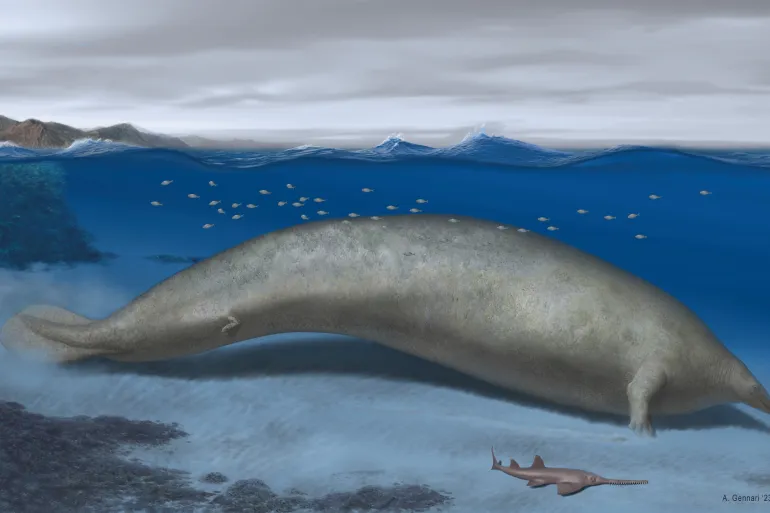

The early whale, which lived about 38-40 million years ago during the Eocene epoch, was built somewhat like a manatee and was likely about 20 metres (66ft) long.

It weighed up to 340 metric tonnes, a mass that would exceed any other known animal including today’s blue whale and the largest dinosaurs.

Its scientific name means “colossal Peruvian whale”.

“The main feature of this animal is certainly the extreme weight, which suggests that evolution can generate organisms that have characteristics that go beyond our imagination,” said palaeontologist Giovanni Bianucci of the University of Pisa in Italy, lead author of the research published in the journal Nature.

The minimum mass estimate for Perucetus was 85 tonnes, with an average estimate of 180 tonnes. The biggest-known blue whale weighed around 190 tonnes, though it was longer than Perucetus at 33.5 metres (110ft).

Argentinosaurus, a long-necked, four-legged herbivore that lived about 95 million years ago in Argentina and was ranked in a study published in May as the most massive dinosaur, was estimated at about 76 tonnes.

The partial skeleton of Perucetus was discovered more than a decade ago by Mario Urbina from the University of San Marcos’ Natural History Museum in Lima.

An international team spent years digging them out from the side of a steep, rocky slope in the Ica desert, a region in Peru that was once underwater and is known for its rich marine fossils. The results: 13 vertebrae from the whale’s backbone, four ribs and a hip bone.

The bones, unusually voluminous, were extremely dense and compact.

Those super-dense bones suggest that the whale may have spent its time in shallow, coastal waters, the authors said. Other coastal dwellers, like manatees and dugongs, known as sirenians, have heavy bones to help them stay close to the seafloor.

No cranial or tooth remains were found, making interpretation of its diet and lifestyle tougher.

The researchers suspect Perucetus lived like sirenians – not an active predator but an animal that fed near the bottom of shallow coastal waters.

“Because of its heavy skeleton and, most likely, its very voluminous body, this animal was certainly a slow swimmer. This appears to me, at this stage of our knowledge, as a kind of peaceful giant, a bit like a super-sized manatee. It must have been a very impressive animal, but maybe not so scary,” said palaeontologist Olivier Lambert of the Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences in Brussels.

Skeletal traits indicate Perucetus was related to Basilosaurus, another early whale that was similar in length but less massive.

Basilosaurus, however, was an active predator boasting a streamlined body, powerful jaws and large teeth.

“It’s just exciting to see such a giant animal that’s so different from anything we know,” said Hans Thewissen, a palaeontologist at Northeast Ohio Medical University who had no role in the research.